Human culture, people’s beliefs and behaviors are shaped by the natural environment we live in. Climate defines our diets and clothing habits, but certainly the most intricate interactions occur at deeper levels – deserts or jungles, the closeness to big waters or high mountains determine the way we perceive ourselves and others and feel about this strange thing called “life”.

Forests take almost 40% of the territory of Belarus [1] making the country one of the 10 “forest-states” of Europe. And, logically, for centuries this natural phenomenon has been playing its own role in defining the specifics of Belarusian nationality—for example, reflected in the fact that up to now we are described as “the most pagan of all the Christian and the most Christian of all the pagans“. Pagan traditions and rites are a natural part of our everyday life, we still worship water, stones, and trees—literally every group of villages has their own “sacred center” (which of course they’d never reveal to an outsider). Magic can live in a stream with healing or killing water, hide a burial hill underground, talk from an ancient tree, or grow alongside with a special “living stone”—all these phenomena are recognized as mighty autonomous entities and peculiar portals of contact with supernatural forces. However, as the history of the county shows, people’s reliance and faith in the support of the forest and bog were something that brought very tangible results—saving lives.

Forests and bogs continued being “places of power” during WWII, during Nazi Germany’s military occupation from 1941-1944. Earning the name of “partisan-republic”, Belarus (back then the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic) became a platform for an unprecedented underground partisan movement. According to the Ministry of Defense, by the end of 1941, about 12,000 people, grouped into 230 partisan units, were fighting the invaders. By 1944, the overall number of partisans reached 374,000. [2] On the one hand, dense forests and marshes made it difficult for the Wehrmacht to pursue the insurgents, on the other, they provided those who were hiding in their thicket with shelter and basic food.

However, the image of the Belarusian partisan was not something associated exclusively with the heroic deeds of the people of the past. A number of contemporary artists and researchers also addressed it in the 2000s, finding in forest introverts the best metaphor for internal individualist underground resistance during Lukashenko’s regime—“guerilla warfare without open battles—quiet partisan life imperceptibly flowing across the official culture”, as the artist and critic Sergey Shabohin puts it in his article “Regeneration in Partisan Conditions”. “The image of partisan is popular both in the official and independent Belarusian culture. But while in the official culture partisans are romantic heroes, whose image is endlessly disseminated in the Belarusian cinema and television for patriotic prevention, guerilla warfare became a survival strategy in the informal culture,” Sergey concludes. [6]

A perfect illustration of parallel realities of the official ideology and hidden resistance movement can be found in Igor Tishin’s photo-project entitled “Light Partisan Movement” where partisans are depicted as if frozen in time, seemingly puzzled and passive (albeit, on the alert). The apt symbol gets detailed interpretation in one of the texts produced by the artist Artur Klinau who suggests viewing these new partisans as people who exist “out of system” and aim not at ruining it, but at “physically preserving their culture code and, if possible, enlarging the territory of their presence” [7]. In such images, forests and bogs populated by the partisans are shown as the places where one has a chance to shift the focus from open (probably unsuccessful or exhausting) combat to self-preservation and self-care—the metaphor that unexpectedly appears to be extremely topical to the current condition in Belarus.

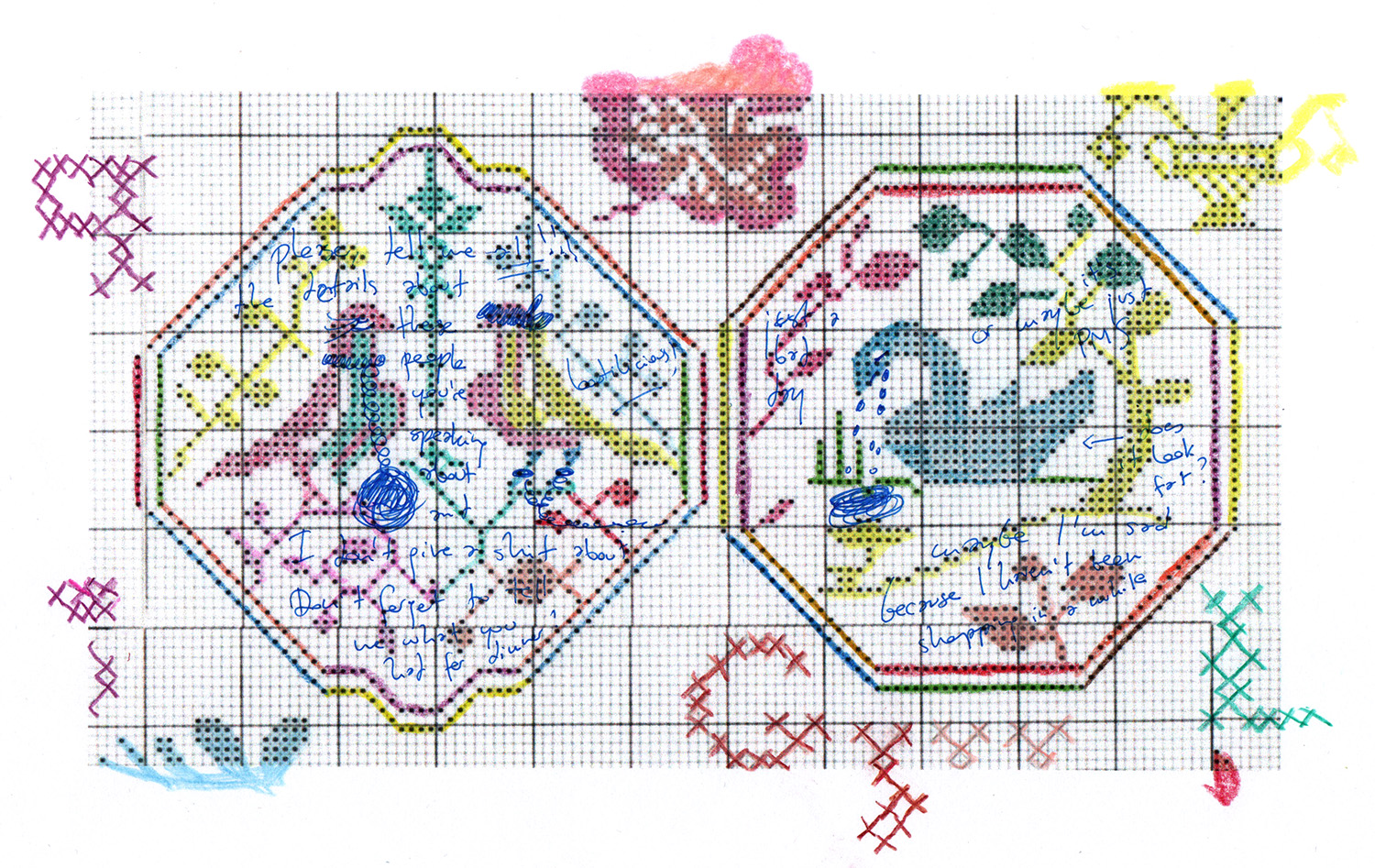

Forest as a resource space is also described in the essay “Silent Hunting” by the Belarusian researcher Inha Lindarenka published in one of the latest issues of “pARTtisan”—the alternative magazine dedicated to contemporary Belarusian culture (actually, the feminine ka suffix was added to the title of that very issue to highlight that it included only texts written by women and queer authors) [3]. In her text Inha addresses human/forest interaction and tries to find ways to “invite forests—not just to visit, but to invite it in order to be attached to life in general and get rid of «hierarchical thinking founded on our general disregard for the assemblage in which we are an element among others»” [4].

Formally the essay is built around the practice of mushrooming (the practice of hunting and collecting mushrooms) which Inha deconstructs by sharing her personal memories and embedding them into a larger philosophical and cultural discourse. The forest, in her writing, appears to be a meditative mystical dimension – that is not only a safe shelter but also a space for collective coexistence of generations of not only people, but also all kinds of natural and supernatural creatures and entities. A place where “the law of the forest operates”, which states that “nothing leaves, it just gets replaced”. [4]

This very ritual of silent hunting seems to match the concept of horizontal parallelism of lives evolving in the welcoming forest and bog environment. “Each of us was enjoying solitude, but still we were feeling close and united. We were shouting each other’s names from time to time to ensure no one was lost. “In-ha-a-a-a-a-a!” “O-o-o-o-ou!” the critic recalls her mushroom family experience. Thus, the need for self-preservation and territory enlargement within the caring space of forests and bogs, proposed by Artur Klinau more than 20 years ago, continues to be topical for Belarusians, who escape and get lost in their literal and metaphorical forests to feel united and supported—by their sisters and brothers, close and distant relatives and neighbors, those who passed away and those not yet born.

The territory has become enlarged—due to the harsh repression now taking place in Belarus under Lukashenko’s regime, many are forced into immigration gradually transforming the entire nation into contemporary nomads. Others have to use the strategy our grandparents had mastered and have moved back to the “underground”. Our forest keeps growing with the distance between us getting bigger—however, just like Inha’s family while mushrooming, we continue shouting each other’s names to ensure no one is lost.

In one of her interviews given in early 2000s, the Belarusian writer and Nobel Prize winner, Svetlana Alexievich, defined herself as cosmopolite, explaining that after Chernobyl one feels his or her kinship not only with any human being, but with a bird in the forest. I dream of the forest one day truly becoming a common space where any person, regardless of their nationality, race or gender, would experience connection with everything alive, would feel respected, rested and loved. Because people and trees really have much in common. Like trees, we are rooted in our individual and collective past. Like trees, we grow new branches, wait for shoots, and cherish the fruit—we reach for the sky and the sun. Like trees, we long for care.

1 – https://www.belta.by/economics/view/lesa-zanimajut-pochti-40-territorii-belarusi-384050-2020/

2 – https://jamestown.org/program/the-partisan-movements-in-belarus-during-world-war-ii-part-one/

3 – http://partisanmag.by/

4 – http://forestjournal.org/v11/silent_eng.html

5 – https://www.instagram.com/anna.bundeleva/

6 – https://shabohin.com/Article-in-English-Regeneration-in-Partisan-Condition

7 – http://partisanmag.by/?p=855

8 – https://www.jstor.org/stable/40922270

Words by Olga Bubich

Olga Bubich is a Belarusian freelance journalist, photocritic, and photobooks reviewer, translator, photographer, and lecturer. Her photographs have been shown in group and solo exhibitions in Germany, Sweden, Italy, Holland, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. As a freelancer, she has collaborated with a number of Belarusian, Ukrainian, Russian, European and American media, among which are birdinflight.com, photographer.ru, journalby.com, partisanmag.by, and many others. Since 2000 she has volunteered at the charity organization “Hope for the Future”, accompanying groups of Chernobyl children to Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Canada. She has been a member of the “Month of Photography in Minsk” since 2014.